Notes on Azerbaijan: Part I

The Land of Fire

Introduction

I have to begin by crediting my favorite amateur travel-writer, Matt Lakeman, for establishing the style and tone that inspired this travel essay. I hope that it will not feel shamelessly copied. For those desiring to read about more adventures in some of the roads less traveled by Americans and other westerners, I cannot recommend Lakeman’s blog enough.

This travel essay will be one-part travel log and one part social, political, and ethnological analysis. I spent around three and a half months in Azerbaijan during the fall of 2023. Most of that time was spent living in the capital city of Baku, but I also took excursions to just about every major region of the country, save for the southwestern region of Karabakh, and the exclave of Nakhchivan that is separated by the border with Armenia.

Some notes on spelling and nomenclature. When I use the term “Azerbaijani”, I am referring to ethnically Turk citizens of Azerbaijan. Evidently some Azerbaijanis just refer to themselves as “Turk”, but for people not from the region this will be incredibly confusing. When I am referring to ethnic minorities or ethnic Azerbaijanis elsewhere, I will try and make that clear. I use “Azerbaijani” instead of “Azeri” because 1) the latter seems to sometimes refer more specifically to people from Iranian Azerbaijan and 2) a very small subsection of Azerbaijani nationalists seem to dislike the word “Azeri” as an Iranian imposition, improperly associating them with the Old Azeri Persian speaking forebears of the region. In most cases you are fine using Azeri, but to be safe I wanted to be particular on this.

In the case there is one, I will default to using the most standard English-language place names for the ease of my mostly-Anglophone audience, and only in the cases that there is not a commonly used English word will I use the standard Azerbaijani names (so Karabakh instead of Qarabağ, and Baku instead of Bakı, etc.).

I have tried to place appropriate “epistemic guideposts” on things I say that were merely purported to me, that I learned from observation, or that I learned from reading sources. This is so you know to what degree you should put trust in any particular claim I make. I am not a professional academic and this won’t read like it, for the present I am just a dilettante with a keyboard and some cool interests.

Elephant in the room time. I was in Azerbaijan for the end of the long-running Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict that is one of the few things many people in the west might know about the country. I had initially planned to do a brief explainer on it here, but since I’m too much of a nerd to cover history with any brevity, I decided to do it more justice in an upcoming Part II: A Short Long History of the Armenia-Azerbaijan Conflict. If you would be especially interested in a deep dive on the history, ethnography, politics, and culture of the Middle East and Caucasus, Part II is for you.

Overview of Azerbaijan

Most of this information is from the CIA World Factbook, with links to elsewhere if it is not.

Capital - Baku

Population - 10,420,515

Land Area - 82,629 sq km (a little smaller than the US State of Maine)

Real GDP - $146.305 billion (2021 est.)

Real GDP Growth Rate - 5.6% (2021 est.)

Real GDP Per Capita - $14,400 (2021 est.)

Median Age - 33.8 years

Life Expectancy - 74.9 years

Human Development Index - 0.745

Total Fertility Rate - 1.993 children per woman

Independence - 28 May, 1918 (from Transcaucasian Federative Democratic Republic/Russian Empire), 18 October, 1991 (from the Soviet Union)

Religion - Muslim 97.3% (predominantly Shia), Christian 2.6%, other <0.1, unaffiliated <0.1 (2020 est.)

Language - Azerbaijani/Azeri/Azerbaijan Turkish (92%).

(Note - Azerbaijan is a very bilingual country, with many people also being fluent in Russian or a regional ethnic language.)

Ethnicity - Azerbaijani 91.6%, Lezgin 2%, Russian 1.3%, Armenian 1.3%, Talysh 1.3%, other 2.4% (2009 est.)

(Note - Azerbaijan recently experienced a mass exodus of the Armenian population in the formerly disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region with the conclusion of the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict. In addition, the age of this census means that the ethnic ratios have likely shifted in the last decade and a half. There are claims that minority numbers are significantly underestimated. I simply do not know how to assess these claims, but I will discuss Azerbaijan’s various minorities later.)

On the Ground in Baku

I would describe Azerbaijan’s culture and “feel” as a perfect blend of Soviet and Middle Eastern (especially Persian and Turkish). When one arrives in downtown Baku, one of the first things to notice is the mixed architectural influence. The more chic locales near the Caspian Sea strive for a belle-epoque Parisian look, mixing wide boulevards for cars with walkable touristy areas with western brands and tourist trap shops underneath some gorgeous neoclassical facades. Some of these buildings are remnants of the days of German businessmen and the Russian Empire, or from Soviet high culture, but I got the feeling that most of the construction was rather new. Downtown Baku also shows many of the touchstones of a modernizing Middle Eastern petrostate, with the enormous glass colossi of the Deniz Mall, Flame Towers, and Port of Baku showcasing a more modernist, futuristic side of the city.

The further you move away from the bougie city center, the more you will encounter cramped alleys and commieblock-style constructions - the sort of dismal grey brutalist apartment blocks you might stereotypically associate with the Soviet Union. In the intermediate Baku neighborhoods of Nasimi, Ağ Şeher, and Yasamal, many older constructions are hidden by modern glass apartment developments. As you move into the more working class neighborhoods further east on the Absheron Peninsula or the northern suburbs like Xırdalan, the more you might feel like the Soviet Union had never ended, with their lines of old Khrushchevka apartments and Ladas parked on the street. I personally lived in an 80s Khrushchevka and found it to be quite charming (aside from the stairwell climb, the enormous door with its rusty lock, and the claustrophobic Soviet elevator that I studiously avoided for fear of getting trapped in a brown-out). I was told by locals that much of the time Soviet constructions are preferred and more expensive compared to modern luxury apartments, because they are seen as safer in the case of fires, earthquakes, and the like.

Baku’s traffic is one of the other things you will quickly notice. It is also one of the things Bakuvians like to bitch about the most. Baku drivers somehow manage to perfectly combine aggression and reactivity, constantly trying to force their way around traffic (sometimes onto sidewalks or shoulders or parking lots) and having to stop for other cars and the odd-pedestrian trying to navigate the deathtrap boulevards. In the many places where there aren’t well-marked traffic crossings or underpasses, you will simply have to wait for a lull in traffic or make firm eye contact with the approaching drivers in each lane as you boldly cross. Crossing the street is a constant balancing act of asserting your dominance, and weighing how likely it is a given driver will assert theirs and choose death for this particular foreigner. That said, these are the rules of the road and people will generally stop for a pedestrian whose purpose is clear.

I can’t imagine having to commute by car in Baku. The metro network in the city is pretty clean and well-maintained, and many stations try to follow the example of the Moscow metro with its ornate decoration, but there are only two main metro lines (really one that splits into two) with a couple of places it branches off. This means that it is usually packed, as from Həzi Aslanov to 28 May stations everyone has to take the same train, and most people continuing would stay on that train all the way to Dərnəgül station.

Most places any visitor would want to see are pretty walkable from the train stations, but there are exceptions, and when you’ve been walking for half an hour and braved three death-trap avenues by shadowing locals, you start to wish there were more stations. I was told by Bakuvians that the Baku metro is the way it is because a lot of the underground space below the city is taken up by oil pipelines and related infrastructure.

Another option for public transportation is the bus, but other than the regular route to and from my place of residence I never bothered to learn the bus routes. I also usually found it more convenient to walk, because buses suffer from the malaise of Baku traffic. Nonetheless, they are clean, and the people very well-behaved by American standards. Both the bus and metro are very cheap options, and you can get a public transport card at any metro station. For a last comment on public transportation, note also that if you are a young man, like myself, you will find that you will rarely be able to sit down on a bus or train. This is because it is socially expected for you to give up your seat to women (of any age) and older folks. I suppose you could also play the stupid foreigner card and keep the seat, but be prepared for some dirty looks.

For taxis, download the Bolt app. Bolt is an Estonian ride-sharing app that is popular in the Caucasus, taking up most of the market share over the likes of Uber and Yandex. It is very cheap and pretty reliable, but be prepared for communications issues if you aren’t at an easily locatable place and you don’t know Russian or Azerbaijani. Avoid the Yango taxis - they have a bad reputation for drivers, including some being drunks.

In Baku, a westerner will find most of the creature comforts they are used to at home. Some things are considerably cheaper than in a western city, especially food and rent, while others cost around the same when converted across currencies, especially coffee and clothing. Many foreign items are only available in the markets in Port of Baku, and for considerably marked-up prices. Most young people in Baku buy their clothing second hand off of a Turkish app called Trendyol that blew up during COVID, since clothing stores are so expensive. Shipping internationally is expensive and generally you would have to ship to a drop-off point rather than having a personal apartment mailbox.

Brown-outs happen in Baku, but are not frequent. The water is pumped in from the Caucasus into a reservoir outside the city, but is not potable despite it not being from the (filthy) Caspian Sea. People either have water purifiers or buy enormous jugs of purified water. Something I noticed in my apartment block is that some neighbors would leave out water containers to be filled by other neighbors who had water purifiers, implying that their possession was not universal but also showing the still-present communal qualities of Soviet apartment blocks.

As far as the areas outside of Baku go, they all have their own local flavors. Many of them were shaped by various local ethnic groups, which we will discuss in more depth later. During the Soviet period, most everywhere in the countryside was organized as a kolkhoz collective farm. Nonetheless many of the villages in the mountains feel decidedly ancient, with barely any Soviet touches, while many of the larger cities like Ganja look very Soviet. Sumgait in particular was once the picture of a Soviet cosmopolitan workers’ city (if also a polluted, deracinated industrial zone, whose economic basis disappeared in the flames of ethnic conflict and logistical collapse). Some like Quba are very intermediate, with medieval or Safavid era structures mixed with Soviet monuments.

For travel between cities, your best option is probably taking the bus from the bus station in Baku near the 20 Yanvar metro station. To get out to smaller towns, though, you will need a driver. Tour groups exist to a lot of the desirable-to-visit towns in the countryside, which I would recommend looking into. You can also find personal drivers or guides willing to take you into the country, if you can get a contact. The train from Baku isn’t really useful for getting around the country, it is mostly for freight rather than passengers. I think it can get you to Ganja and Lankaran, but lacks the versatility of other options.

İçerişeher

The old, inner city of Baku, İçerişeher, is a beautiful and quaint place that showcases some of what Baku used to be, as well as providing some revealing pictures of the ways it has changed. In the eastern bloc, İçerişeher was famously showcased in the 1969 Leonid Gaidai comedy movie The Diamond Arm, where a hapless Russian tourist is accidentally given a cast containing valuable diamonds by some smugglers operating from an İçerişeher pharmacy. In the film, the (even-then touristy) district looks considerably dustier and run-down, with prostitutes and groups of dirtily-clad children running about the streets. Much of this was exaggerated by the movie, of course, whose setting was not explicitly Baku but some vague eastern city the tourist was traveling to, and I doubt it had poverty at the level portrayed by the film, but nonetheless the simple look of the streets has changed significantly.

İçerişeher today is manicured cobblestones and rows of parked Mercedes (with some very fashionable rugs sometimes thrown over to keep the interior cooled), and sizeable groups of Russian and South Asian tourists being carefully led by their guides up the Maiden Tower and about the porticoes of the Shirvanshah Palace. The famous pharmacy from The Diamond Arm is now a cafe, and street merchants near the (rebuilt in the 20th century) gates will heckle you to take pictures wearing Caucasus shepherds’ hats or Soviet ushankas, or to buy pricey oriental textiles.

All this said, İçerişeher was my favorite place in Baku. It still gave me a calm, authentic vibe when I went to sit there at night watching the bay and hearing the call to prayer ring from its antique mosques, when I escaped the tourists’ haunts by walking around the maze of alleys petting cats and sitting in gardens as I felt the cool winds blow off the Caspian, and while sipping tea and eating baklava watching the sun set on the walls. However much it might try and exploit and commercialize its oriental mystique, I still found that İçerişeher was a meeting point for past and future. Its ancient monuments and modern hotels demonstrate Azerbaijan’s growing sense of self-esteem in holding the symbolic connections to an idealized past, as well as a magnet for the world outside to find something of worthwhile interest in it.

The main monuments in İçerişeher require tickets that can be bought around the neighborhood at kiosks. Prices are significantly higher for foreigners.

The Baku Maiden Tower is old, but no one knows exactly how old, with some legends painting it as a remnant of a Sassanid-era Zoroastrian shrine, or a medieval Shirvanshah fortification. The other monuments include caravanserais and the Shirvanshah Palace, which has gorgeous grounds and a small museum, and a cute miniature book museum. There is also supposedly a section of castle at the bottom of the bay in front of the district, but I didn’t bring my snorkling gear and the Caspian Sea south of the Absheron is an ecological disaster zone.

I was also told the still-running ancient hamam, or Turkish bath, in İçerişeher was very high quality. Hamams function kind of like spas in the west but with hot and cold rooms and with a big Turkish guy who beats the crap out of your back instead of a masseuse. I was too chicken to go, unfortunately.

Post-Soviet Politics of Azerbaijan

I will cover some of this in more detail in Part II, but I will quickly run down the political situation in Azerbaijan post-independence here. Most of the information here comes from Thomas de Waal’s excellent book Black Garden.

Meet the Aliyevs

Azerbaijan is in many ways a typical post-Soviet autocracy, with the heart of politics being found in the influence of the Aliyev family and their courtiers. I do not think that it is flippant to describe Azerbaijan’s presidency as dynastic. Prior to independence from the Soviet Union, most of the Azerbaijani state apparatus was already in the formal or informal control of Heydar Aliyev, who would become the man to shape its post-independence future. During the late USSR, Heydar was a KGB major general who developed some smart connections and ended up appointed as First Secretary of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan, later serving as the only Azerbaijani member of the Politburo throughout the 80s. After falling afoul of Gorbachev during the latter’s perestroika and anti-corruption campaigns, Heydar was removed from the Politburo in 1987 on alleged health reasons. Heydar’s informal connections in Azerbaijan, which he had left in the hands of his capable lieutenant Abdurrahman Vezirov when he left for Moscow, began to find themselves challenged by nationalist independence activists and the conflict with the Armenians.

Heydar Aliyev returned to Azerbaijan in 1990, where he soon established a fiefdom for himself in his native Nakhchivan to hole up for the coming storm. The Baku governments of Gorbachev-implant Ayaz Mutallibov, and then pan-Turkic nationalist and dissident ideologue Abulfaz Elchibey, successively foundered under the conditions of complete systemic collapse and military defeat that faced Azerbaijan in the early ‘90s, while the USSR crumbled around them and the Armenians invaded Karabakh. In 1993, Elchibey was overthrown in a coup after he botched the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict and failed to tame separatism, corruption, and the economy. Afterward, the military turned to Heydar Aliyev as the logical choice to take over the reins of the state.

Aliyev Sr. began stabilizing Azerbaijan’s situation by purging Elchibey’s people from the government and military, winning an election against a couple nobodies, admitting defeat to the Armenians and signing a ceasefire in 1994, and surviving an attempted counter-coup in 1995. Aliyev began playing a diplomatic game of getting all the major world powers to recognize de jure Azerbaijani suzerainty over the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh, with conditions to be worked out…eventually. This would end up paying dividends to the Azerbaijanis, as it permitted them to play the long game on the disputed territories.

On the home front, Aliyev put together a commission that wrote a new constitution that solidified the country as a unitary presidential state with a parliament and judiciary he could control. This established the legitimacy of his new regime, after which he could tackle corruption and deal with the huge refugee influx coming off the conflict by establishing state subsidies for all Azerbaijanis from the occupied territories. Internationally, he maintained warm relations with both Russia and the United States, establishing a route for oil export through the Russian port of Novorossiysk that allowed him to finally start bringing in some revenue. Heydar Aliyev died in office in 2003, passing the reins off to his son, Ilham Aliyev, who ran in the elections for that year.

Ilham’s first election was seen by outside observers as full of irregularities, including ballot-stuffing, arresting the opposition, controlling the media and obstructing election monitors, all the good stuff. He won in a landslide, of course. This is all pretty predictive of how Azerbaijani elections would continue to go over the next twenty years, just with less required coercion as Ilham’s presidency became a simple fact of life. Ilham just won another election this year by another landslide margin.

I also would be remiss if I did not point out that Ilham really doesn’t pull off the militaristic irridentist dictator look. While he is tall and has the beefy Caucasus wrestler build, he has a heavy slouch, has low energy in his speeches, and overall projects his personality like a limp noodle. Definitely a backroom micromanaging workhorse kind of autocrat, rather than flairy African strongman or passionate interwar European irridentist. Please just watch him give this one rousing speech attempting to exult in his Karabakh victory - he is truly trying. Compare this to a high-energy post-Soviet leader like Lukashenko…

He doesn’t need to be that kind of leader, though. Ilham is a smart man - effectively the scion of Soviet nobility, he received a doctorate of history and taught at Moscow State Institute of International Relations, which is something of the IR school of Russia’s Grand Ecole while also serving as their equivalent of the Foreign Service Institute. He got the benefit of an influx of western expertise and the first generation of newly foreign educated Azerbaijanis to run his system, permitting him to dispense with many of the old Soviet apparatchiks. I would highly recommend this Palladium article which goes more into detail on Ilham’s role in creating today’s Azerbaijan.

Under his dad, Ilham served as vice-president of the state oil company SOCAR and brokered the deal with the western oil companies that brought them, with their markets and expertise, into the Azerbaijani oil industry He later also secured the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline through Georgia and Turkey, which permitted significantly higher exports of Azerbaijani fuel to global markets. Ilham used the growing oil wealth to create a massive international slush fund and engage in “caviar diplomacy” outreach efforts to secure international recognition for Azerbaijan’s claims on Nagorno-Karabakh, as well as isolating the Armenians. Aliyev critically managed to butter up the United States in the wake of 9/11 by making Azerbaijan indispensible to the American logistics network in Afghanistan. He secured significant arms deals with Turkey and Israel. The latter is also a close intelligence partner and market for oil, making Azerbaijan unique among majority-Muslim countries in its coziness with the Israelis. All of this culminated in an increase of tensions with the Armenians over the 2010s and finally the long-awaited Second Nagorno-Karabakh War in 2020, which ended indisputably in an Azerbaijani victory, and then the final reclamation of the whole region in 2023.

Ilham is also known for…taking care of his friends. He has cultivated a small group of oligarchic families who control large portions of the economy and receive a nice cut of the country’s oil wealth, by his graces. Some of the most famous examples include the Pashayevs, the family of his wife Mehriban, who dominate the country’s banking industry with the help of the state’s antitrust authorities, as well as the family of Ziya Mammadov, who used his position as Minister of Transportation to rack up massive construction contracts for his companies. Much of the proceeds from these contracts ended up in the Azerbaijan Laundromat corruption scandal that served as an important arm of the country’s caviar diplomacy initiatives.

One fascinating story I heard about while in Azerbaijan was that of Trump Tower Baku. Seemingly, Donald Trump’s construction company may have failed to do its due diligence in choosing local construction partners, one of Ziya Mammadov’s companies, and ended up lending their brand to a luxury hotel in a very un-luxurious area of Baku and from which the money invested may have been embezzled and gone into the hands of Iranian intelligence assets. Oops. I tried to find the location of the Trump Tower site as recorded on Google, but when I got there I discovered only a fish restaurant and some apartments, and ended up getting lost in Narimanov.

Ilham and Mehriban have three children - Leyla, Arzu, and Heydar. Leyla and Arzu jointly own the telecom Azerfon, as well as their grandfather’s holding company PASHA Holding, and a number of Panamanian offshore companies. They are both married to prominent Azerbaijani/Russian socialites of oligarchic families, and also own tens of millions of dollars in property in Dubai and Moscow.

Heydar Jr. is remarkable in that he may be the heir apparent (with the constitution being amended in 2016 to remove the age requirements for the presidency to make way), while also having comparatively far less media spotlight than his sisters. He also owns millions of dollars worth of property, but information on him personally seems to be rather sparse - his mother soft launched his wedding on Instagram to some mysterious unnamed bride, the identity of which is assuredly the subject of much Azerbaijani gossip that I am not particularly privy to. What rumors I’ve been able to find on the Azerbaijani internet speculate about the wife being Ukrainian, and also the possibility of Heydar Jr. being kept out of the public eye because of some kind of cognitive impairment.

I think the picture we get of Ilham Aliyev is ultimately that of a pragmatic Machiavellian prince. I heard it said on one occasion that he governs the country like a CEO - if Aliyev is a CEO, he is a very corrupt one who would have had a lot of problems with the SEC. He might also be a war criminal because of the 2022-23 Karabakh blockade and ultimate departure of over 100,000 Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh. But I get the analogy. He is unideological, certainly not like Elchibey was, but he tactically deploys nationalism to drum up popular support, while ensuring the loyalty of Azerbaijan’s elite through personal patronage. The return of Karabakh is a wave he will ride for years. He cuts a very fine line in international diplomacy by making deals with whomever he needs to fend off threats like Iran, without any permanent commitments being made to anyone save perhaps Turkey. He is a hard man, but you can’t say he doesn’t know how to distribute the bread to his advantage. I expect to see him remain in power in Azerbaijan for years to come.

The Personality Cult of Heydar Aliyev

Despite the current long-lasting presidency of Ilham, there is something of a personality cult around Heydar Aliyev as the man who saved the nation in the 1990s. I don’t know if it is a conscious imitation of Ataturk in Turkey, but I feel like there are some similar notes and I wonder if the Ataturk cult of personality felt as weird in, say, the 1960s. Heydar’s image was everywhere in Azerbaijan - you saw a bust to him in every office building and school, half the public buildings in the country seemed to be named after him, and 2023 was declared the “Heydar Aliyev Year” by his son Ilham to celebrate Heydar’s 100th birthday. Enjoy a small selection of Heydar-ography that I have collected over my months in Azerbaijan:

I don’t want to put too fine of a point on this, but Heydar is important to the state mythology of Azerbaijan. I think it was also prudent of Ilham to make his father the foundational figure of the Azerbaijani state. It helps anchor his regime in place and time, helps the country build a national myth, and dead men don’t make mistakes. There’s also the matter that Ilham himself cuts a poor figure for being the object of a personality cult.

Nationalism, the War, Irridentism, and the Cult of the Martyrs

On September 19, 2023, the news was suddenly all abuzz about a jeep being blown up by a mine along the Nagorno-Karabakh line of contact. This kind of crap happened there every week since the ceasefire in 2020, with sporadic gunfire or the odd shelling or mine detonation, but all of a sudden the Azerbaijani government and media was making a big ruckus about this jeep. It was self-evidently a seized casus belli for an operation that had likely been in the planning for quite a while. Azerbaijani forces began saturating the remaining territory of the Artsakh Republic/Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast with artillery and advancing their infantry. The Karabakh Armenians, cut off by the Yerevan government of Nikol Pashinyan after the war in 2020 ended in an Armenian defeat, were forced to sue for peace. The terms were the complete surrender of arms and the total dissolution of the Republic’s government. The so-called Third Nagorno-Karabakh War barely lasted two days.

It is estimated that 800,000 Azerbaijanis were evicted from the territory occupied by the Armenians after a cycle of brutal and mutual pogroms and ethnic cleansings in the First Nagorno-Karabakh War of 1988-1994, which had ended in an Armenian victory. Most of those refugees or “Internally Displaced Persons” (IDPs - a term for refugees who did not take shelter in the borders of a foreign state) had ended up in Baku, where vast refugee camps formed on the periphery in the ‘90s. I met several IDPs in my time in Baku, most now moved on into big city professional life. Some refugees got apartments subsidized by the government, some of these claimed from those of Armenian families who had been killed or fled in the 1990 Baku Pogrom. I will delve more into detail on all of this in Part II.

All of this is to say that the conflict was omnipresent in Azerbaijan. The Nagorno-Karabakh War is the national trauma. And the Azerbaijanis, much like their Turkish cousins next door, are a nationalistic people in the best of times. Every neighborhood or village in the country displays the pictures of their şehidler, or “martyrs” - veterans who had given their lives in the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict. I believe that civilian casualties are also counted as şehid. Localities see the number of şehidler they produce as a matter of pride - in Ganja, I saw thousands of memorials lining the main boulevard as I came in. I am told Sumgait has something similar.

Nothing tops the Şehidler Xiyabanı, or Alley of the Martyrs, though. This is the national cemetery, comparable to Arlington Cemetery in the United States. There are rows and rows of Azerbaijani officers and war heroes, as well as some civilians, covered in flowers in the shadow of the Flame Towers. Funeral custom in this part of the world is to put a portrait of the dead on all gravestones, meaning their faces are all staring at you while you walk by. At the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, the President of Azerbaijan also likes to give speeches to stand with the martyrs behind him when trying to drum up patriotism. School groups frequently visit to lay flowers at the graves, often with the children wearing military uniforms.

The presence of the war pervaded in other ways, too. Many Azerbaijanis insist that this was not an ethnic conflict, but merely a legal and territorial dispute over the status of an autonomous province in the hands of rebels. The general attitude towards Armenians hinted somewhat otherwise. Antipathy to Armenians was omnipresent - Baku once had a large and thriving Armenian community, but most of their monuments had been erased. The only things left were the abandoned church in the Fountain Square, now denuded of all Christian imagery, as well as some now-defaced cemeteries noted by Thomas de Waal in Black Garden. In 1990, the Baku Pogrom took place, during which dozens of Armenians were killed and the vast majority fled into exile. Local ethnographic work always contained a serious hard line about the Armenians as foreign to Azerbaijan. People were distrustful of European countries in understanding the conflict, assuming that majority Christian states would always side with their brethren and that Azerbaijan could only trust countries like Pakistan and Turkey who supported it for identitarian reasons.

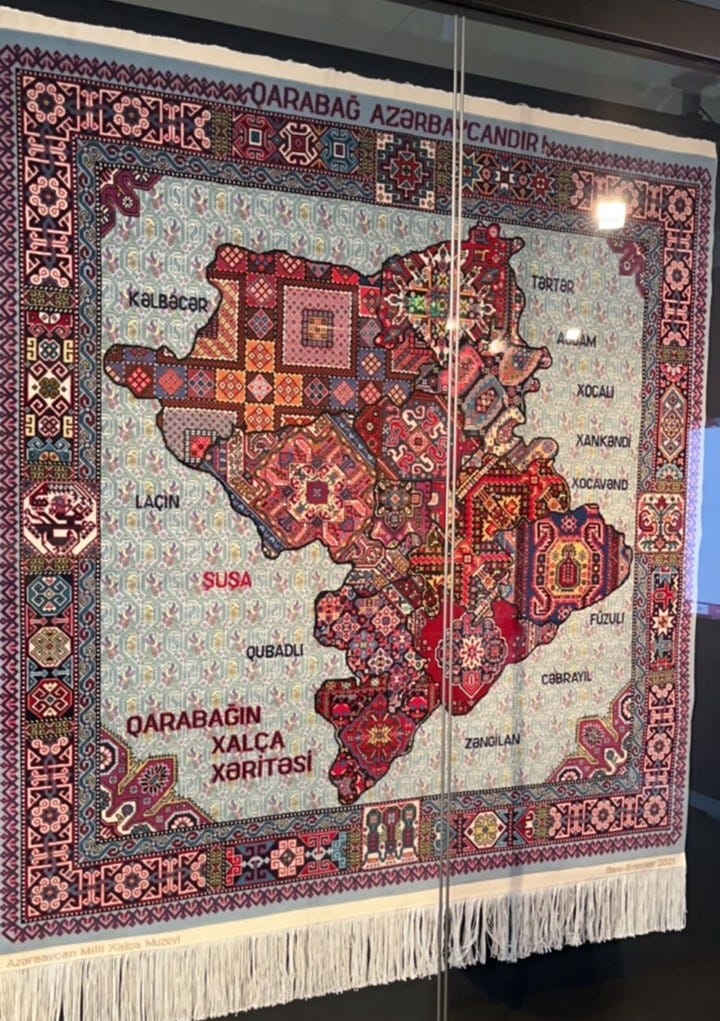

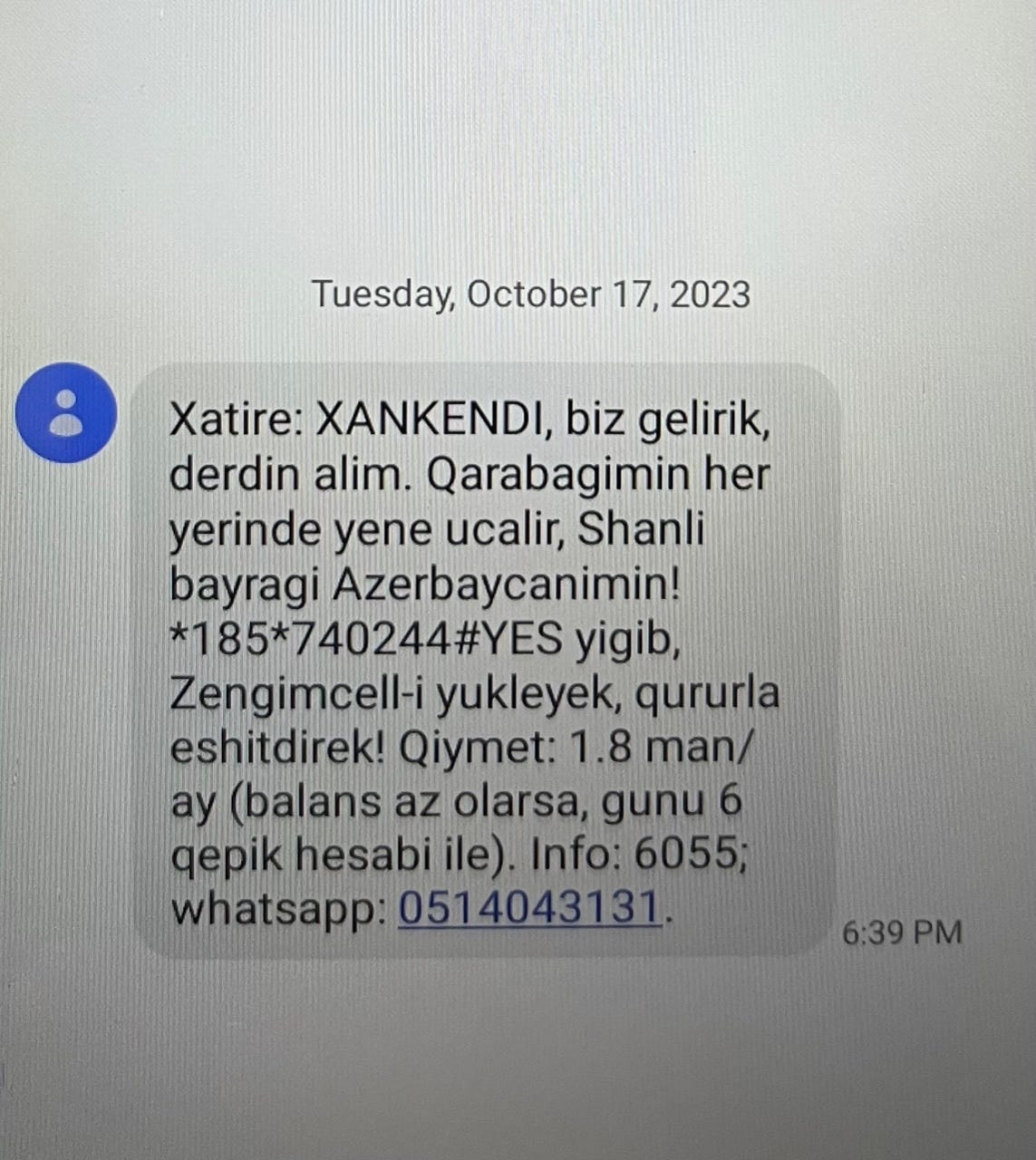

The symbolism of Karabakh is everywhere, too. Maps of the lost territory are omnipresent, from carpets to construction tarps. An orchid called called the xarıbülbül, which only grows in the historically Azerbaijani city of Shusha in Karabakh, became a symbol of the martyrs and soldiers who had fought to retake the city in 2020, and sits on the corner of most newscasts as well as on items from advertisements to lapel pins to tissue boxes.

After the Artsakh Armenians surrendered, the Azerbaijani military began a slow march towards the regional capital of Stepanakert, which the Azerbaijanis know as Khankendi. During this march, a panic swelled through the Armenian population while the Azerbaijanis conveniently reopened the Lachin Corridor that gave access to Armenia. A mass exodus of 100,000 people ensued, for fear of retribution from the Azerbaijanis. The official government line was that all Karabakh Armenians would receive equal citizenship under the law. In the light of the bloodshed of the ‘90s, the long-running cyclic violence, and general atmosphere of hatred, I think that the flight of the Karabakh Armenians was a reasonable response to a credible fear of violence from the Azerbaijanis. I do not think the assurances of safety from the Azerbaijani government were credible - the Armenians of Sumgait and Baku had full legal equality as well, which did not save them when the mobs came and the police looked away. After all I’ve seen and heard, if I was an Armenian, I at least would never be able to feel safe in Azerbaijan. For better or worse, the Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict is finally over.

I was also in the country for Victory Day, which in Azerbaijan is no longer celebrated over Soviet victory in WWII. It is now in honor of the Karabakh Conflict and was moved to the 8th of November - two days before the ceasefire that ended the second war in 2020 was concluded, so as not to conflict with the anniversary of the death of Ataturk in Turkey (something that points to the close spiritual relationship shared by the two countries). I would argue that the Cult of the Martyrs of Karabakh in Azerbaijan has largely replaced the Soviet Victory Cult you still see in places like Russia or parts of Central Asia.

The Victory Day parade for 2023 took place in recently-retaken Khankendi, so unfortunately I was unable to go. Nonetheless there were pretty vibrant celebrations in Baku as well. I took a stroll along the Seaside Park where they had massive screens up showing the parade and festivities in Khankendi, while all the men who had completed their mandatory military service were out wearing their old uniforms, and people draped themselves in Azerbaijani (and Turkish) flags while watching the fireworks kick off. Some old timers were out drinking with their units reminiscing on the first war, back in the ‘90s.

As a last note - Azerbaijanis and Turks are stridently nationalistic peoples, and have a curious relationship to each other. Azerbaijani flags lined the streets in Baku, and I would say that around half the time they were twinned with Turkish flags. Heydar Aliyev came up with this formulation of relations between the two countries of “One Nation, Two States” and people take this very seriously in Azerbaijan. The Turkish embassy is huge, Turkey’s president Erdoğan visited for Victory Day in 2020 while Turkish military units joined the parade, many Azerbaijanis have work or family ties in Istanbul, they have a bilateral military alliance…it is kind of hard to understate how close Azerbaijan and Turkey are. I would compare the relationship to Russia and Belarus.

Political Culture in Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan has elections, a legislature, a judiciary, all that good stuff, but most of it is pretty centrally controlled by the political establishment. Civil Society in Azerbaijan is functionally nonexistent. Nonetheless, I think Aliyev has some amount of fear of a Color Revolution like Ukraine’s Euromaidan. Towards the end of my time in Azerbaijan, Samantha Power had made the government angry after questioning the conduct of the Azerbaijani military in the war, after which the government began putting pressure on USAID and embassy programs in the country while cracking down on journalists. I think part of this also may have been in preparation for the snap elections Aliyev had called.

Street corruption isn’t really a thing in Azerbaijan, and neither is street crime. I never had to pay a bribe in the country, and had heard no stories of other people having to. Police are very common, and every street is under surveillance - actually, most businesses, schools, and office buildings have cameras as well. The police seem perhaps a little more personable than in the US - I heard a story from a friend about their observations of a Baku traffic stop, which involved the guy getting out of his car and an hour long conversation ensuing with the cop that ended in them hugging it out and them both driving off with no tickets involved. On one corner I passed frequently there was always a tough-looking policeman carrying a submachine gun, who nonetheless one day I observed picking flowers in the bushes to give to a little girl. It was an odd vibe.

Every expat I spoke to about it also reported how remarkably safe they felt on the streets of Baku - some of this from people who had been in dozens of countries. Bakuvians all pretty much completely dismissed the threat of street crimes in the country. Police are pretty omnipresent, and fights are taken care of very quickly. To my knowledge, owning guns and carrying knives are illegal, and in a country as small as Azerbaijan that is probably pretty enforceable. Before going into a train station or government building, all bags have to go through an x-ray like you would see in airport security in the US. I don’t know if it’s Japan-level “leave your bag on a bench and return to find it the next day” level of social trust, but the chances of you getting mugged are very low. Through street violence is rare, domestic violence seems much more likely to be frequent and also harder to go to the law for. Capital punishment isn’t used in Azerbaijan, but I got the impression that incarcerations are frequent and harsh. Prison radicalization seems to be a problem in Azerbaijan - I suppose that will happen when you throw all the radical mullahs in with the convicts…

Drugs are very, very illegal in Azerbaijan. Nonetheless, the Baku metro stations have a bunch of anti-drug ads, which implies that it is an extant problem. Drug addiction and homelessness is rarely visible on the streets (I saw one man visibly strung out on the subway, and later saw him again passed out by the Philharmonie about 20 minutes later - the police were on it quick). I think it can be presumed that most such people are incarcerated. I smelled marijuana once at a semi-isolated restaurant in a town south of Baku on the Caspian, but on no other instance. If you do ever smell drugs, immediately start moving in the opposite direction because the police can ring you in for being nearby as well.

While street-level corruption may not be much of a thing, Azerbaijan is infamous for its high level corruption. I have already gestured about the power of Aliyev’s oligarch allies, and while you may never have to pay a bribe to a policeman or bureaucrat on the daily, my instinct was that if you actually found yourself in the legal system that could change remarkably quickly. I also took it that it is not easy to succeed in business beyond owning a small corner shop if you do not have the right friends and butter up the right officials.

Azerbaijan’s economy is very oil dependent, and has been for a very long time - oil and natural gas made up around 60% of the government budget and 90% of export revenue as of 2021. This means the Azerbaijani economy is very vulnerable to shifts in global commodity prices, and also that it is vulnerable to the resource curse wherein a country remains impoverished because its state infrastructure becomes focused around exploiting resources to the detriment of other parts of the economy. Since Azerbaijan’s oil is in oligarchic possession, this means a lot of the oil wealth remains in the hands of the rich and foreign companies, and out of the hands of working-class Azerbaijanis.

I was listening to gossip from some of the British oil expats in Baku, and learned that Azerbaijan is pushing localization policies on the UK oil companies. Basically they were saying that they were having to train their own replacements, who would be native Azerbaijanis, and that they would be leaving in a year or two. In any case, it seems the government is cognizant about the issues of the distribution of the windfall from the country’s oil industry. There has also been some noise made about the necessity of economic diversification in the country. Interestingly, Azerbaijan is hosting the COP29 climate conference this year, which struck me as either wildly hypocritical, purely diplomatic, or a sign of the necessity of change in the way energy and economics works in Azerbaijan. Maybe some of each.

Young people in Baku seemed to be pessimistic, overall. Many of the ones I talked to wanted to move to Germany, or America, or maybe Turkey or Russia if their ambitions were less high (though these countries also have pretty abysmal opportunities for zoomers these days). They often dislike the Aliyev regime because it doesn’t provide much in the way of economic opportunity and saps away most of the oil wealth for pensioners and corrupt oligarchs, while the young receive basically nothing. Meanwhile, the job market in Baku isn’t terrific. Unskilled labor costs are very low because of how glutted the market for labor supply is. I noticed a ridiculous amount of beauticians in particular, given the lack of much else to do and women in Baku desiring their services so much. Many pretty well-degreed people (by the country’s standards) end up stuck in the service economy.

This mostly seemed to manifest in an apolitical cynicism and a desire to leave. Political dissent is basically a pointless endeavor there, Aliyev has support where it counts and I won’t even bother litanizing the times that the government has suppressed opposition - just go google “Azerbaijan arrested journalist” or “Azerbaijan arrested dissident” and you will get a picture. There is an opposition but it has to toe a very fine line or find itself being suppressed. Elections are obviously shams. For disaffected people, there’s a depressive feeling that change isn’t going to be coming any time soon and they will just have to live with the hand they’ve been dealt or move.

Azerbaijanis seemed pretty mixed on the Soviet legacy, all things considered. Some of the older folks certainly exhibited some more “sovok” tendencies, but it was not as strong as you might find in Belarus, Russia, or Kyrgyzstan. When I asked one older person whether things were better back then, I got a shrug, and some discussion on how the Soviets took better care of poor people overall but there was more wealth in the country all-around and more freedom. With Heydar Aliyev in charge so soon after independence, whose influence had been the guiding hand of Azerbaijan through most of living memory, I’d imagine for many people Aliyev’s return felt like a return to normalcy, coming with a feel of continuity and a sense of “the more things change, the more they stay the same”. The touch of Soviet culture and politics runs deep in Azerbaijani society, but people don’t seem to look back on the USSR with much in the way of explicit nostalgia. Most of the old Victory Cult monuments over the Great Patriotic War have been repurposed around the Cult of the Karabakh Martyrs, with many renamings and alterations of monuments.

Older folks also tended to be apolitical, but generally more positively disposed to the regime. In one case, I was told “I hope you enjoy Baku - it wasn’t always like this…”. I presume this was referring to the modernized neighborhoods and luxury goods and services, with a hint of undertone about the really dark things that happened there at the close of the Soviet Union. I think most of those who were of age during the 1990s are appreciative of the stability brought to the country by the Aliyev regime, as well as their handling of the Karabakh issue and the increasing outward signs of development. They tended to not talk about domestic politics much, instead preferring to project a lot of that energy into talking about foreign affairs and the Armenians.

Speaking of which, the future of the Armenia-Azerbaijan question is still very much open. Now that Karabakh is settled, Aliyev seems to be pushing on the Zangezur corridor to link Nakhchivan with the rest of Azerbaijani territory by land. There has already been some fighting that is a bad portent for the future, since Azerbaijani troops violated Armenia’s internationally recognized territory in 2021. Nikol Pashinyan, the pro-western Armenian president, has basically reacted by being a wet noodle for the Turks and Azerbaijanis and capitulating on whatever he can, lacking firm support from Moscow or elsewhere to stand on.

There have been ongoing talks about giving Azerbaijan land access through Syunik/Zangezur, or to permit land access to Nakhchivan through Iran. The Azerbaijanis I spoke with seemed to be happy that the conflict was over and didn’t favor a reopening of war with Armenia. This one would also look a lot different globally considering Syunik is internationally recognized as part of Armenia. The time of more or less inviolable international borders may be coming to an end, however…we’ll see. At least in the short term, it looks to me like Aliyev can get what he wants in terms of securing Nakhchivan’s logistics through a combination of bluster and negotiation. Hopefully an agreement will be reached and the two countries can start to consider what a normal relationship will look like in the future.

Azerbaijanis, their Culture, their Social Norms

Azerbaijan is, at one time, both a very secular and very conservative country. Much like many of the other majority Muslim areas that were formerly part of the Soviet Union, religious practice is seen largely as a private thing in Azerbaijan. Laicite is strong, proselytism is illegal. Nonetheless, most people profess Shia Islam, and cultural norms are heavily influenced by it.

Despite there being legal gender equality, many places in Azerbaijan have a kind of soft gender segregation. The best illustration of this is in the concept of the çay evi or çayhane - tea houses. To a western ear, a tea house might sound like a vaguely effeminate or archaic environment for old ladies to tastefully discuss gossip. I assure you that in the Middle East it is nothing of the kind. The çay evi is like the pub, there is one on nearly every street, and it is a place for the boys to go hang out, smoke, play tavla or dominos, and sip on tea and eat candy bars. Some even have video game systems you can pay to play, and have what might be considered e-sports tournaments. It is actually a remarkably relaxed environment, and interesting considering that in the US it is hard to find a place to hang out after around 9:00 that isn’t a bar. Perhaps another part of the appeal is that women basically aren’t permitted in them - to my knowledge, there is no law saying this, it would simply be a break of social protocol.

A lot of the businesses like cafes and restaurants also have a soft gender coding, but not nearly so clear or strong as at a çay evi. Sometimes coffee shops and cafes will cater to a more female clientele, or there will be two restaurants of very similar type right across the street from each other that have more male or female customer bases. This is something you will just have to “vibe” when you get there, and consider where gets you weird looks and where doesn’t. Gender-coded businesses are a thing in the US too, of course, but not ones where the clientele is entirely men older than 40 who will give rude glares if you have a woman at your table, as well as nearby cafes to meet the female market.

If you look at groups of grade-school and university-aged students, it is remarkable how they all seem to cling to mono-gendered cliques and almost form a straight line across a courtyard between them, in a way evincing much more than the easily recognizable nerves of adolescence. Friendships between single men and women are also less common than in the west, both from observation and from what was attested to me. I was told by some women I knew that Azerbaijani men will almost always make a pass at them after a first meeting out of pride, but if rebuffed in the right way could become platonic friends.

I would say that roughly a quarter of Azerbaijani women regularly wear headscarves outside of the mosque. Most people are generally lax in their prayers, and the call to prayer cannot be heard or is difficult to hear in much of the city. Unmarried women generally live with their parents, and often have strict curfews or might be expected to be accompanied by a male family member if they are out late. Alcohol is legal in Azerbaijan and highly available (vodka is absurdly cheap), and the streets have a constant scent of tobacco smoke from the qaqalar chilling with their bros smoking on the street. Use of both alcohol and tobacco is seen as a marker of promiscuity in women, however, and so at least publicly it is usually only consumed by men. At one private dinner I went to, I found myself doing shots of straight vodka in the Russian style (with a long toast before every shot, Caucasus-style…) with all the men of the family on one side of a long dinner table, while the women and children clustered on the opposite end of the table consuming more innocent drinks and having a separate conversation.

Arranged marriages are still basically regular in Azerbaijan, though they are subtler than you might think from stereotypes Americans have about them in e.g. India. To be unmarried is a sign of being defective the more you age, with concern starting to show after around age 25. Usually in your upper 20s if you have not found a spouse yet, your family members will start intervening to find you one. When you meet a married woman in Azerbaijan, usually her first question after “what’s your name?” and “where are you from?” is “are you married?”, after which she may start gesturing about a niece or cousin you ought to meet...on one occasion, I was asked if I would convert to Islam to marry an Azerbaijani woman in what I took to be a not-entirely hypothetical question. The first meeting between two older women might include an exchange of information about single male and female relatives for consultation among the Azerbaijani grandmother network. For a man with male friends, they may offer to set you up with their friends’ sisters or female friends, but very rarely a female family member of their own.

I was told that bride kidnapping (qız qaçırmaq) is still a thing in parts of the countryside, but also that in actuality it is mostly symbolic and really looks a lot more like what we would call elopement. In these cases it is more a staged situation where the bride is “in on it” and has agreed to a marriage, and the kidnapping is acted out for traditional or financial reasons. In any case, it seems to have been declared illegal under Azerbaijani law, which implies that it is not seen as an entirely innocent practice.

I’m still not entirely sure how most courtships (and they are usually courtships, casual dating still seems to be frequently frowned upon) in Azerbaijan come about, considering that I did not do any dating while in the country to know firsthand and there is so much social distance between men and women. I guess from an introduction through this second-hand relationship networking thing that goes on? In any case, life finds a way, and virtually every park bench in the country during warm weather is occupied by a canoodling teenage couple, presumably trying to liaise outside the eyes of their overzealous relatives. A courtship in Azerbaijan usually is pretty short by most American standards, with about three or four months going by before the girl’s male relatives start coming by and making progressively less subtle gestures about putting a ring on it. Cohabitation is basically unheard of.

Azerbaijani women tend to be very well-done up. From what I understand, going out without a coat of makeup is seen as a sign of sloppiness and liable to get a lady some mean glares from the xanımlar on the street. They also tend to be well-dressed, usually with the shoulders covered. Norms for clothing are less conservative in the bougie parts of Baku, as these areas are more western in all respects. This includes the practical non-existence of the soft gender segregation for most establishments there.

Women can be seen in full face veils in Azerbaijan, but I have been told that these are more often foreigners from the Gulf or Iran or the Subcontinent visiting with their husbands. One of the most jarring things I saw was a man wearing a ratty t-shirt and jeans next to his wife, who was completely covered head-to-toe in a niqab - they looked possibly to be from Pakistan.

I was told before coming to Azerbaijan that women tended to only wear heeled shoes, but I think this was a changing norm, as sneakers were worn with pretty much anything. I never saw women wearing athleisure, and gender-segregated gyms are very common - this time, for the women’s convenience. Women often wore beautiful scarves that variously served to keep them warm, to be a headscarf if they were to enter a mosque or church, and simply as a fashion statement.

Baku women have something of a reputation for being mean. I personally only encountered this when a barista laughed at some of my early attempts at Azerbaijani. Some of the western women I knew reported that some of the female solidarity they were accustomed to in the west did not exist to the same level in Azerbaijan, and that women in Baku had a habit of viciously tearing each other down beyond the standard limits of western intrasexual competition. I heard some young Azerbaijani women in Baku who had experienced life elsewhere complain of this as well.

One thing Azerbaijanis like to remark on is that the first Azerbaijan Democratic Republic, which was briefly independent from 1918-1920, was the first majority Muslim country with constitutional democracy and legal equality for women, and that it also gave women the right to vote before the United States did. I find that countries in which women’s rights (as well as other forms of civil rights) were instituted by the decree of a modernizing regime, as opposed to by civil agitation, tend to have a very different way of operationalizing those rights and baking them into the social fabric. The activist energy isn’t nearly so constant - certainly in part because activist energy in general will not do you any favors with the authorities.

Men in Azerbaijan tend to wear all neutral colors (usually black, grey, or blue), with jeans or slacks. One individual I knew from Turkey liked to call the groups of Azerbaijani men who sat around talking on the street “penguins” for their clothing, which was generally pretty on the nose. Their hair is always short, often-times with the stereotypical Middle-Eastern/South Asian dude fade and sweepback. While beards are common enough, they are short and well-trimmed so as not to make you look like a hyper-religious hodja. Older men love their mustaches. There was one older Azerbaijani dude I knew who, whenever he would see me, would interrogate me as to when I intended to get a haircut. Usually letting my hair grow out a little bit, and not wanting to have to explain how to cut my hair to a barber in a way that would not have me come out looking like Hasan Piker, I had been neglecting this. This is evidently a cardinal mistake in Azerbaijan.

Azerbros also tend to use pretty copious amounts of cologne, which mixes in with the smell of the cigarette smoke throughout the day. On that note, this is a phenomenon - on every street and most porches, you can see groups of Azerbaijani men just chilling, having a smoke and shooting the shit, at all hours of the day. I don’t know if they just don’t work? The word for “bro” in Azerbaijani is qaqa, pronounced “gaga”, which is supposedly a corruption of the word for brother through some really lazy enunciation (qardaş→qahdagh→ qaqa). The Russian brat might also be used.

Women also frequently seemed to be more educated than men were. I encountered numerous anecdotes of well-degreed women who worked as engineers or bureaucrats or librarians or what have you that also did the traditional housewife stuff on the homefront, while the husband worked as a taxi driver or did Bolt food deliveries or chilled with his qaqalar smoking at the çay evi all day.

Traditional clothing in Azerbaijan is very beautiful. Today it is most commonly worn in traditional weddings, in which the bride wears a red sash to symbolize her virginity (something that is supposedly becoming controversial in some feminist circles, as the norms around pre-marital sex have started to shift?), and the bridesmaids and groomsmen generally wear versions of the traditional garb. I unfortunately did not have the opportunity to go to an Azerbaijani wedding while I was there, but I hear that they are quite the blast where the family rents out a giant ballroom, there is virtually infinite food, and nearly as much dancing. I’ll attach a video of one below, as well as a video made by a government-funded media center with Azerbaijan traditional dance and clothing.

Gender norms for foreigners are a bit different - especially for women. For whatever reason, foreign women in Azerbaijan have a reputation as being more promiscuous, and visibly foreign women (especially blonde Russians) tend to attract more attention on the street than an Azerbaijani woman would. My take on this is that it is because foreign women don’t have male relatives around, so who will come kick your teeth in if you look at her the wrong way? In any case, one recommendation commonly given to foreign women to avoid this is to wear a fake wedding ring. I guess it proves there’s someone there to provide the ass-kick, and the bond of marriage is seen as pretty inviolable in Azerbaijan (though divorce is a common malaise here as in much of the post-Soviet world).

For foreigners of both sexes, the judgment for violation of clothing norms is less harsh. One thing I have noticed is that in many parts of the world wearing shorts can be remarkably contentious, and can often be the signal that most loudly screams “I am a foreigner”. It is said of Russians that, once you put them in warmer weather, they will indulge in it to the maximum of their ability and bring out the flip flops and shorts even if it isn’t that balmy to those of more southerly climes. In Baku this manifested in the often humorous phenomenon of spotting Russian guys by the enormous baggy jorts they would wear around.

Homosexuality is decriminalized in Azerbaijan, but the social censure is at such a degree that “out” individuals are practically unheard of. The word on the street (among western liberal expats) was that there is a small gay community that tends to cluster around international bars in the westernized areas of Baku. Civil society in Azerbaijan being as weak as it is, there is little serious push for gay issues.

Azerbaijanis very frequently have a sense of exoticism about people from other races, especially east Asians and black people. From what I understand, in most of the Soviet world the “n-word” was considered to be a neutral term of description for black Africans, but nonetheless you can tell the contexts in which there is ill-feeling in the use. Black people in Baku will find themselves stared at a lot, and people will often marvel and ask if they can take a selfie if they encounter a black person. Azerbaijanis who are more clued into western social discourse have started to adopt the use of “qara insan”, which literally translates as “black person”.

Azerbaijani women (and women especially, for some reason), if you ever brought up China, Korea, or any of the people or countries from that region, would almost on cue light up with a huge smile and pull their eyelids out to make a squinty face. I had to stifle a laugh at this a couple of times. I actually think Azerbaijanis tend to really like people of other races, but the contact is infrequent and they have some ways of expressing it that wouldn’t be permissible in the west.

Though many Azerbaijanis aren’t necessarily religiously pious, quite a few (especially rural) people maintain an interesting array of traditions and superstitions. One particularly common belief is that exposure to the cold will literally make you sick - the older women of the household will micromanage their family members’ clothing choices in cool weather. I have heard that even doctors in Azerbaijan will subscribe to this. Many older women will keep sage around the household to provide the family with spiritual protection. Some people maintain an interest in traditional Caucasian or Turkic folk traditions. The ancient Persian/Zoroastrian new year holiday of Nowruz is still huge in Azerbaijan. This wiki article on Azerbaijani folklore you can translate is an interesting window onto some traditional myths. Azerbaijani folklore is very regional, and people from one village on one face of a mountain might tell very different legends than those of the opposite face.

One last note on Azerbaijani social norms is that their society makes considerably more room for children than American society does. Kids are a constant presence in Azerbaijan in a way they no longer are in cities in the United States. People are walking with their kids along the streets, playing with them in the parks, there are entire blocks of park dedicated entirely to entertaining children, and many restaurants have play areas for children. Children play football in the street and sometimes walk to school unsupervised. A lot of the sorts of things we hear “back in my day…” about in the US feel significantly more common in Azerbaijan.

I think people have considerably less neuroticism about something happening to their kids in a country like Azerbaijan where violent street crime is virtually unheard of, there are cameras everywhere, police are always within a couple blocks, and where there’s more of a village mentality around raising kids. Extended family and neighbors are very frequently involved in the lives of each others’ kids, visiting each others’ households, inviting each other to meals and celebrations, and the like. Coming back to the United States, I feel that there is probably something pathological about American society that children are so often considered to be a nuisance to be excluded from public spaces, rather than a natural and necessary part of the social body.

Ethnic and Religious Minorities in Azerbaijan

Post-Soviet Remnants

Baku once was a picture of Soviet cosmopolitanism - one neighborhood still bears the name Xalqlar Dostluğu, or “Friendship of Peoples”. A lot of that legacy is gone now - the end of the Soviet Union saw massive population repatriation movements all over, and in Baku this process was accelerated by the chilling effects of the Baku Pogrom on the city’s Armenian population.

Baku Armenians once inhabited an unofficial “Ermenikend” that stretched across most of Nasimi Raion in central Baku, and which in fact left them living alongside Azerbaijanis and others. Thomas de Waal paints Baku’s Armenians as urbane and Russophone. They were known for producing chess grandmasters like Gary Kasparov, who once identified himself as a “Bakinets”, or Bakuvian, when asked his nationality. As I mentioned earlier, not much is left of Armenian Baku save some bashed up cemeteries and a shuttered church. Sumgait and Ganja also used to have substantial Armenian populations that were similarly driven out once the 1988 hostilities started.

The other big, and this time still extant, Soviet community in Baku is the city’s Russian population. I am not conversational in Russian, so my few interactions with Ruslar were short and formulaic. From what I understand Baku Russians tend to live in their own majority-Russian apartment buildings. Baku Azerbaijanis seemed to have a mild sense of dislike towards Russians, some more overt than others. I sometimes felt that Azerbaijanis, particularly more nationalistic types, can have an inferiority complex with respect to Russians - Soviet high culture was normatively Russian, Azerbaijanis effectively lived under Russian rule for around two centuries, and Russians still walk around Baku insisting only on using the Russian language, which remains something of the international language people default to when speaking with foreigners. Much of higher education in the best schools is still exclusively in Russian. I heard a couple of zoomers express a nationalistic sentiment when they said that they did not know Russian. It is also not hard to stumble upon Azerbaijanis and Central Asians on the internet complaining (often in English) about how Russians are misperceived as a high-class culture, when they should be perceived as brutal and barbaric conquerors like we tend to stereotype Russians in the west.

I think much of the antipathy is informed by history and geopolitics, perhaps more than personal negative interactions per se. Azerbaijanis tend to support Ukraine in the Russo-Ukrainian War, seeing comity with Ukrainians in slipping the grip of Moscow and sympathy over a neighbor utilizing separatist sentiment to carve away an integral region of the country. Azerbaijanis and Armenians also have a (frankly kind of amusing) habit of accusing each other of being the real Russian puppet state - the former on the basis of the Russian peacekeepers that intervened in 2020 that kept the Azerbaijanis from taking Stepanakert during the second war, and the latter because they think Putin sold them out after the anti-Russian Pashinyan took power, developing some kind of gentleman’s agreement with Aliyev to let him take Karabakh.

Russians have three Orthodox churches in Baku - I visited two of them. Both were incredibly beautiful and seemed well-attended. They seem to function partially as community centers for the Russians (much as many such diaspora churches do in the US), who would often sit outside for several hours chatting. I got some suspicious gazes from some babushkas when I attended Divine Liturgy once, but I do not think visitors were necessarily a weird phenomenon as I saw some curious Azerbaijanis come in that day as well.

I was told that there are some communities of Russian Old Believers in Quba and Ivanovka, the latter being a Molokan colony. I did not encounter them in Quba and never got to visit Ivanovka.

I never figured out what Russians tended to do for work in Azerbaijan. I never encountered any working anywhere. Many of them seemed to be retired older people - I would imagine many of these are simply people who were here in the Soviet times that never left. I was asked for directions once by two lost-looking younger Russian guys that I thought might have been draft dodgers. The Russian oil behemoth Lukoil was founded by ethnic Azerbaijani Vagit Alekperov, and was one of the few non-Azerbaijani oil companies that seemed to sell fuel in Azerbaijan, which may be part of the story here. Perhaps there is an entirely parallel social ecosystem for Russian oil expats?

Other post-Soviet ethnicities were represented in Baku as well. There were some Georgians who seemed to be there entirely to run restaurants. Georgian food is very popular in the former USSR, though the Georgians and the Azerbaijanis have some classic culinary feuds over things like “who invented khinkali/hengel”. There are a couple of ethnic Georgian villages in the far northwest of Azerbaijan, as well.

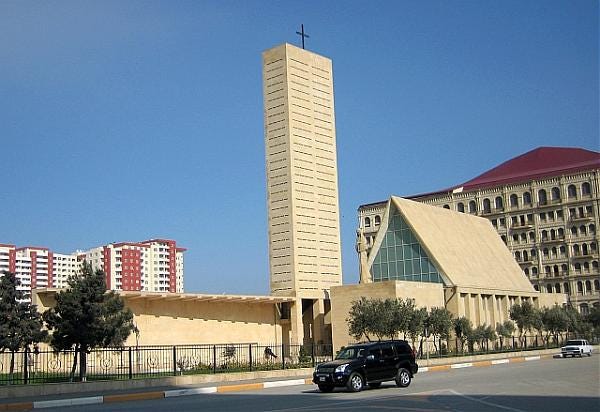

There is one Catholic Church in Baku that was built out of an old Soviet warehouse, where Polish workers used to hide in order to pray away from the prying eyes of the authorities. The story I heard was that it was established with funding from Ilham Aliyev since he and the priest there were old school friends. Pope John Paul II visited at one point, there are some Polish Catholic icons and historical memorabilia. I did not attend a service here so I can’t say whether there are many church-attending Polish Catholics in Baku. I would wager a lot of the current parishioners are western expatriates.

Jews come in two kinds in Azerbaijan - European Ashkenazis and Mountain Jews. Mountain Jews are a fascinating group that I will cover in a moment. Baku Ashkenazis, to my knowledge, arrived during the Russian Empire. You see some Hasidim walking around in Baku occasionally, but their community is by no means large. Both Jewish communities have their own synagogues, which were under heavy guard by police and synagogue-members as I visited the week after the October 7 Hamas attack on Israel - I had to get a pat-down before going into the Ashkenazi synagogue, and there were very visible police all around the block. Somewhat to my surprise, the rabbi there spoke fluent English and was educated in the United States.

Other Foreigners and Expats

Baku had a notable population from the Indian Subcontinent. Azerbaijan has a big fan in Pakistan - a really big fan. Pakistan loves Azerbaijan to an extent that even starts to feel weird and unreciprocated - for instance, Pakistan does not even recognize the Republic of Armenia as a state. Not Artsakh, Armenia itself, which even Turkey and Azerbaijan recognize. What?

In any case, there are some restaurants owned by Pakistanis that I was informed were not bad. Pakistani flags flown next to an Azerbaijani and Turkish one were not uncommon, either to express some gratitude for Pakistani moral support or by Pakistanis showing their love for their adopted home. There are also quite a few Indian and Pakistani medical students in Azerbaijan. I was told by one Indian med student that this was because it was cheaper and easier to get in, since India has a weird system based on its states for getting into medical schools. Some Pakistanis are also in Azerbaijan as a stopover on a longer trip towards Europe.

The biggest non-Eastern Bloc group of expatriates in Azerbaijan seemed to be from the British Commonwealth. A lot of Scots and Africans, in particular. Most of these were people who worked for British oil companies, in various capacities. Due to localization measures I mentioned earlier, I expect this population to decline with time. Many of the non-oil company expatriates worked in things like IT or education. I met several Americans as well - usually working in education or the like, though I’d heard some Texans were kicking around in the oil trade.

Western Protestants will find little to serve their spiritual needs in Azerbaijan, as Protestantism’s history in the country is almost entirely the story of insular German Lutherans who are long gone, and proselytizing in the country is illegal. They have interestingly developed a house church system in some of the expat areas to accommodate this.

I never felt uncomfortable as an American in Azerbaijan. People generally were just very surprised to encounter an American in daily life. Some people were kind of bewildered why I was over there, when so many of them wanted to be over here. Sometimes they were just excited to have someone to practice English on. Some people also had some amusingly misshapen beliefs about America - one person asked me whether I knew any celebrities, and also seemed to think that Black Lives Matter came about because Donald Trump was literally, personally sending policemen to murder unarmed black people. One person I met who had visited America commented that, for living in such a rich country, Americans really dress and eat like shit.

People would often enough ask me my opinion on politics, sometimes just random people on the street coming up and saying “you’re American? Biden or Trump?”, or about some arbitrary foreign conflict like Serbia vs. Albania or Russia vs. Ukraine. It was rare anyone would ask me about Karabakh directly. There was one occasion someone tried to extract a “Qarabağ Azerbaycandır!” out of me, but I think most people were happy to assume that if you were there, you were on team Azerbaijan. I would highly recommend that you not signal otherwise.

I got the feeling that many expats interact minimally with local Azerbaijanis in a substantive manner. Few of the foreigners I’d met had put any effort into learning Azerbaijani - they generally seemed to subsist entirely in the Anglophone expat bubble around Port of Baku, had some Russian, or would learn the minimal amount of Azerbaijani necessary to complete mundane errands.

Someone told me they hung out with a bunch of Colombians living in Baku. I have absolutely no idea what a bunch of Colombians would be doing living in Baku, and I never personally encountered them.

Tourists often came to Azerbaijan from Russia, as well as the Indian Subcontinent and occasionally Europe. I met one American retiree who was there on a group to see the whole Caucasus region. There were a lot of Germans on my flight over going for a cheap tourist destination, but I never encountered them or any other Germans in Baku again - though there are a lot of artifacts left from the time when German industrialists and businessmen were involved in the Baku oil industry, like the Lutheran church, now long a concert hall long without a parish. The town of Mingachevir was also founded in part by German WWII POWs. I met a lovely Italian couple in İçerişeher who were passing through on a business trip and trying to catch as much of the sights as they could, and a couple more older Italians touring Sheki.

Minority Native Ethnics in Azerbaijan

The Caucasus is something of an ethnic freezer - it becomes very clear why this is once you’ve gone on your first road trip in the Greater Caucasus. The roads in the mountains very frequently feel like deathtraps in their own way, with roads that turn to gravel and rock on 60 degree inclines, careening cliffs around every corner, and other cars invisible behind the next bend - some people up here even managed to live driving BMW sedans, which was absolutely baffling to me. In addition to the danger factor, though, it is not hard to see how an ethnic group could remain up here relatively unbothered for much of history, preserving isolated languages and ethnicities while the tumult of history largely passed in the lowlands below. My contact with many of these groups was limited, but I’ll give a short roundup on some of what I find to be Azerbaijan’s most notable and interesting ethnic minorities.

I mentioned the Mountain Jews a bit earlier - they are the autochthonous Jewish population of Azerbaijan that is purported to have been in the South Caucasus since the 5th or 6th century, when they fled north fleeing persecution in the ancient Sassanid Persian Empire. They speak a Persian language called Judeo-Tat, which is a branch of the Persian Tat languages in Azerbaijan that is influenced by Hebrew and Aramaic. They are classed as a branch of Mizrahi Jews. The Mountain Jews tend to cluster in the north, on the eastern most slopes of the Greater Caucasus. Their most notable settlement is the village of Qırmızı Qəsəbə, which is purported to be the last shtetl (majority ethnic Jewish settlement) in Europe. They also have a community in Baku, with its own synagogue.

I think that a large part of the generally positive attitude Azerbaijanis have towards Jews stems from their positive experience with the Mountain Jews. Having been separated from the Jewish mainstream for so long, they tend to resemble their neighbors as much as they do European Ashkenazis, and have a healthy dose of the Caucasus martial spirit. Some prominent şehidler who died fighting the Armenians were Mountain Jews, which earned the community some street cred in Azerbaijan. Memorials to these şehid are very prominent in their synagogue in Baku.

The existence of Judeo-Tats implies other Tats as well, and indeed there are other speakers of Persian Tats languages in Azerbaijan. Tats communities are spread throughout the northeastern mountains of Azerbaijan. There is another subdivision between Armeno-Tats and Muslim Tats, with the former being Tat speakers that practiced Armenian Apostolic Christianity, but they by-and-large have all gone to Armenia or Russia, where their remnants are rapidly assimilating in exile. The Armeno-Tats, already very small and on the way out in the 19th and 20th centuries, is now on the door to being extinct as an identifiable community.

Muslim Tats are also rapidly assimilating into the mainstream of Azerbaijani society, linguistically and culturally, with the numbers of people self-identifying as Tats rapidly decreasing over the 20th century. Nonetheless, the community is still extant. I almost visited the village of Lahıc, which has a substantial Tat population, but the roads conditions were difficult.

I would surmise that the necessary communitarian conservatism and insularity of Jewish diasporas has enabled the Mountain Jews to hang onto their traditions and identity with a higher degree of success than the other Tats-speaking groups of the Caucasus, but nonetheless a large amount of Mountain Jews upped sticks to Israel during the large waves of aliyahs from the Soviet Union in the 1970s and 1990s. There appears to have been some Israeli outreach to this community, with some plaques I noticed in Qırmızı Qəsəbə commemorating visits from Israeli officials. Wikipedia at least estimates their population in Israel to be much higher than in Azerbaijan, but I do not know where they pulled their numbers. I would also be curious to learn about the extent to which they are continuing as an identifiable community in Israel. In any case, the Mountain Jews seem to have the highest profile of all Tat-speaking groups in Azerbaijan.

There is another large community of speakers of a Persian language in the south of Azerbaijan: the Talysh, who span the Iran-Azerbaijan border region and are reputed to descend from the ancient Iranian tribe of the Cadusii. In Azerbaijan, they cluster in the towns of Lankaran, Lerik, and Astara. They have much healthier population numbers than their distant cousins the Tats, with estimates ranging in the hundreds of thousands rather than the single or tens of thousands. Azerbaijan Talysh are also Muslim, and majority Shia, much like the rest of the Azerbaijani population.

They inhabit the most fertile region of Azerbaijan - most of Azerbaijan’s tea is grown in the southern mountains along the border with Iran, and its more Mediterranean climate is good for the cultivation of fruits like oranges, kiwis, feijoa, and quinces. These culinary and climatic factors, as well as its picturesque Hyrcanian forests and Talysh Mountains, a sub-range of the Iranian Alborz, makes the territory popular for tourism.